The difference between “theory” and “experiments” is not very well defined in climate science. A “theoretical” paper almost always includes results from simulations (experiments) with idealized numerical models. Are these models “theories”? How complete does a model have to be before it is no longer “theoretical”1? On the other hand, given that we only have one climate system, we can’t conduct experiments with it: efforts to increase CO(_2) concentrations are not driven by scientific curiousity. Maybe exoplanets should be thought of as the natural set of specimens available to us, which we can probe and dissect, but our ability to observe these is still limited and it is not always clear what studying them can tell us about Earth’s climate. The same issues come up with paleoclimate.

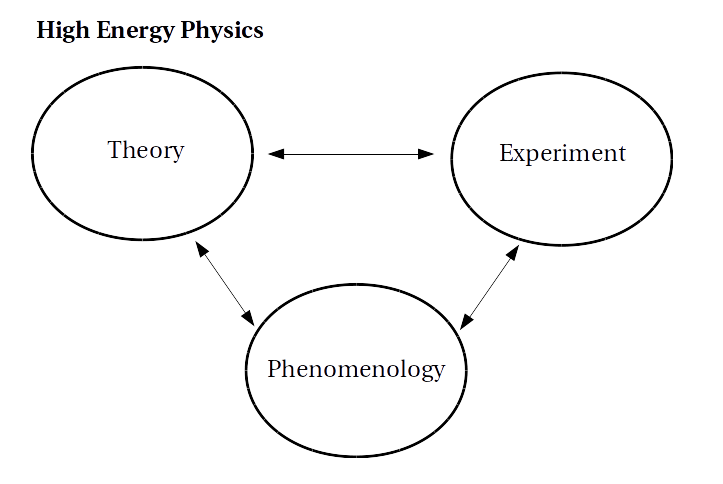

Given these ambiguities, I think it's interesting to compare with high energy physics (HEP). As I understand, HEP can be divided into three sub-disciplines: theory, experiment and phenomenology (see sketch). Theoreticians study string theory, quantum gravity, etc., and work entirely in theory-world. Meanwhile a huge number of people design and build experiments like the LHC to test these theories. Some of them might describe themselves as physicists, others as engineers; I'm not sure how the distinction is made. Finally, phenomenologists come up with ways of testing the theories and interpreting the experiments. For instance, how to actually interpret the output of the LHC to say whether the Higgs particle exists or not.

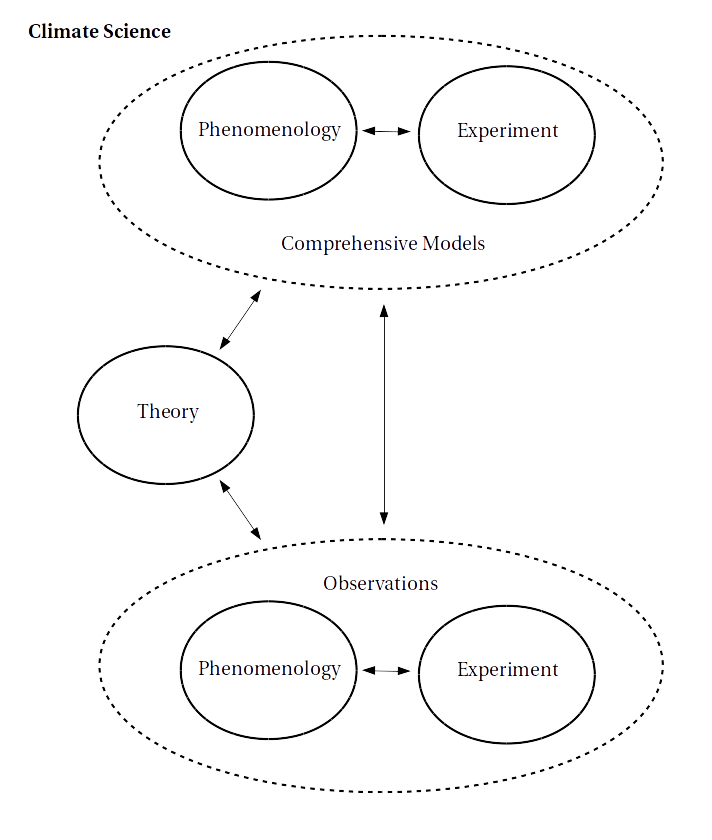

In climate science the divisions are less obvious, but I think it's still useful to think in this way. The first distinction I would make is between theory, climate models and observations. "Theory" here is both theory in the sense a theoretical physicist would use it and results from idealized numerical models, while "models" means the comprehensive climate models used to inform policy and to predict the weather.

Next, for both models and observations the same distinction can be made between "experimentalists" and "phenomenologists". For models, the experimentalists are the model developers and the phenomenology is the analysis of simulations. This could be to predict warming by the end of the 21st century, to test the ability of climate models to make decadal predictions, to develop emergent constraints on climate sensitivity, etc. On the observational side, the experimentalists build satellites, measure carbon fluxes, gather paleoclimate data, ..., while the phenomenologists again analyze the data.

A key difference between climate science and HEP is that climate scientists can move between the different divisions whereas HEP physicists cannot (or at least not as easily). A climate scientist might start in one area and then move to another over the course of a career, they might work on multiple projects with different aims, and a single project can include aspects from separate areas: model development and analysis, or theory and observational work. There are people who are focus only on model development, or who only work on theory and idealized numerical models, but the majority probably work on a mix of things.

Individual climate scientists have to decide where they want to position themselves. An important part of this is their relationship to the modelling centers (often government labs) which develop the comprehensive models. Obviously if you want to develop climate models you have to be affiliated with a modelling center, and if you want to analyze model data it's also useful to good working relationships with people who work at a modelling center. Similar considerations apply to working with observations

For myself, I find my work so far to be a combination of theory and phenomenology. I've worked on some very idealized problems, some problems involving observations and others involving data from comprehensive models. I like that these different problems require different ways of thinking and that I can move back and forth depending on my mood. This speaks to the freedom of climate science, and the benefits of working in an interdisciplinary field.

-

This is not just an issue in climate science, most fields now combine theory with idealized simulations. ↩