Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) are one of the main tools used by policy makers to predict the economic impacts of climate change. For instance, they played an important role in determining the Paris Climate Goals, and are used by the US government to estimate the “social cost” of carbon (SCC). It’s worrying then that they’ve been criticized recently for drastically underestimating the potential risks of global warming (see David Roberts’ article on Vox for a summary).

The technical reasons for the shortcomings of IAMs can get involved, but some of the critiques raise an interesting question that is more fundamental to thinking about climate policy: how can we make decisions in the face of large uncertainties? And not just large uncertainties, but what are sometimes called “subjective” uncertainties?

What Are IAMs?

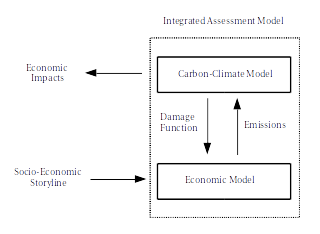

IAMs are made up of a simplified model of the carbon-climate system coupled to a “general equilibrium” economic model:

The economic model predicts carbon emissions, which are fed to the carbon-climate model, and the climate model estimates a “damage function”, which is given back to the economic model. Together, these can be used to explore the economic impacts of socio-economic storylines. For instance, we could compare a “business-as-usual” storyline with a future in which there is aggressive mitigation, and see which scenario results in the higher overall economic growth.

IAMs combine models for two systems we can’t model very well: the climate system and (even worse) the economy; so their results come with a lot of uncertainty, and they’ve been described as "close to useless as tools for policy analysis". But they’re still the best tool we have for predicting the potential economic impacts of climate change and they actively inform policy decisions, so we need to take criticisms of them seriously.

Subjective Uncertainty

We can divide up the sources of uncertainty in IAMs into “objective” uncertainties and “subjective” uncertainties. On the climate side, climate sensitivity – how much the Earth will warm up for an increase in CO2 concentrations – is an objective uncertainty. We can run experiments with a set of climate models and then use the distribution of their sensitivities to get a best estimate of Earth’s climate sensitivity and also to put error bars on this estimate. The only places where human judgment comes in are in whether to exclude bad models and in how to calculate the error bars.

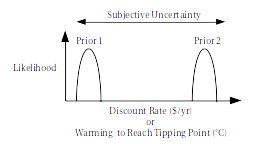

An example of a subjective uncertainty is the question of how close we are to any “tipping points”. For instance, global warming could cause the meridional overturning circulation in the ocean to suddenly shut off, which would be a disaster for society. But we don’t have a precise idea how close we are to this actually happening, whether it would take 2 degrees of warming or 8 degrees. This isn’t the only tipping point that we know of, and the others are all similarly unconstrained.

Another way to put this is that our estimates of the tail risks of climate change are basically educated guesses.

Things get even worse on the economic side. An important subjective uncertainty is the discount rate: how much we want to push the costs of climate change onto future generations. Taking a steep discount rate means that we expect future generations to come up with technological innovations to deal with the effects of climate change, and we shouldn’t worry about emitting carbon today. A low discount rate leads to the opposite conclusion, and says that we should be doing everything we can to reduce carbon emissions.

This isn’t something with a “correct” answer, but it has a huge impact on projections of climate change impacts: Pindyck (2017) suggests that much of the difference between Nordhaus (2008)’s estimate of $20/ton for the SCC and Stern (2007)’s estimate of $200/ton comes from differences in their assumptions about the discount rate.

The general issue of subjective uncertainty is also referred to as the issue of having multiple priors (really multiple non-overlapping priors):

Intuitively, multiple priors are likely to come up whenever an uncertainty is poorly constrained and so people’s opinions and biases come into play when quantifying it.

Uncertainty In IAMs

How do IAMs deal with subjective uncertainty? Basically by ignoring it. IAMS use “expected utility functions” to integrate over their uncertainties, but the utility functions are based on the judgments of the people building them and only consider a single prior (this is why the estimates of the SCC by Nordhaus and by Stern are so different).

They also ignore the tail risks on the climate side, predicting that even large warmings will have relatively small economic impacts. The thinking seems to be that since we don’t know how close we are to any tipping points, IAMs shouldn’t take them into account. And it’s actually worse than that, since they also omit the effects of climate changes that are hard to quantify economically, like ocean acidification (more here).

So IAMs both underestimate the risks of climate change and the uncertainty of their predictions. This isn’t an ideal situation.

How Can We Account For Subjective Uncertainty?

There has been some recent theoretical work on how to extend the expected utility framework to include multiple priors (see here and here). The simplest way is to replace the expected utility functions with “max-min” expected utility. This means policies are compared based on their worst-case outcomes, considering all of the priors.

This can be made more elaborate. For instance, we could combine the best and worst outcomes of each policy (e.g., 0.6 x the worst outcome + 0.4 x the best outcome) or weight the outcomes by our (subjective) estimate of their likelihood.

Whatever choice we make involves ethical decisions about how we want to handle risk. The max-min approach is the most risk-averse method of evaluating policy options, and speaks to the preference people have for “ambiguity aversion” (“better the devil you know than the devil you don’t”). If they felt as though there was a non-negligible (say 5%) chance of disastrous climate change, then people would generally prefer to take the certain cost of paying today over the uncertain cost of betting on the potential of disaster.

The opposite would be a “max-max” approach, which would take the best possible outcome of each policy, and would be a heavy bet against climate change having major impacts.

Because IAMs currently ignore tail risks and subjective uncertainty, pretty much whatever we do to incorporate these into IAM studies will increase how much damage we expect climate change to have, and we really need to start doing this. I’m not sure what the best way of accounting for them is (max-min seems a bit too cautious), but it’s clear we can’t just ask “what impacts could this policy have?” and have to include a preference for how risk adverse we are, or else who’s (subjective) opinions we trust the most.

Perhaps the most important thing is that however subjective uncertainties are accounted for, this choice must be clearly communicated to policy makers. If the result of a max-min study suggests we should be urgently reducing CO2 emissions, the people making decisions should be clear that this is based on a comparison of worst-case scenarios. It might even be better to take this further and have policy makers choose in advance how to balance risk-aversion with subjective estimates of uncertainty in studies of future climate scenarios. Since they're the ones who will make the decisions, they should be involved in modeling the potential impacts of these decisions.