A major open problem in atmospheric dynamics is what causes the eddy-driven mid-latitude jets to shift polewards under climate change and, conversely, to shift equatorwards during strong El Nino events. This is seen in idealized models and in comprehensive climate model simulations of future warming scenarios, though more clearly in the southern hemisphere than in the northern hemisphere (where there’s more land). Understanding these shifts is important scientifically and for society, especially as they affect the location and severity of extreme weather events in mid-latitudes.

A closely related question is what causes the tropical circulation to widen and contract in these scenarios (see here for a recent review). These two phenomena might be related, but I’m not going to get into that here, and only focus on the jet shifts.

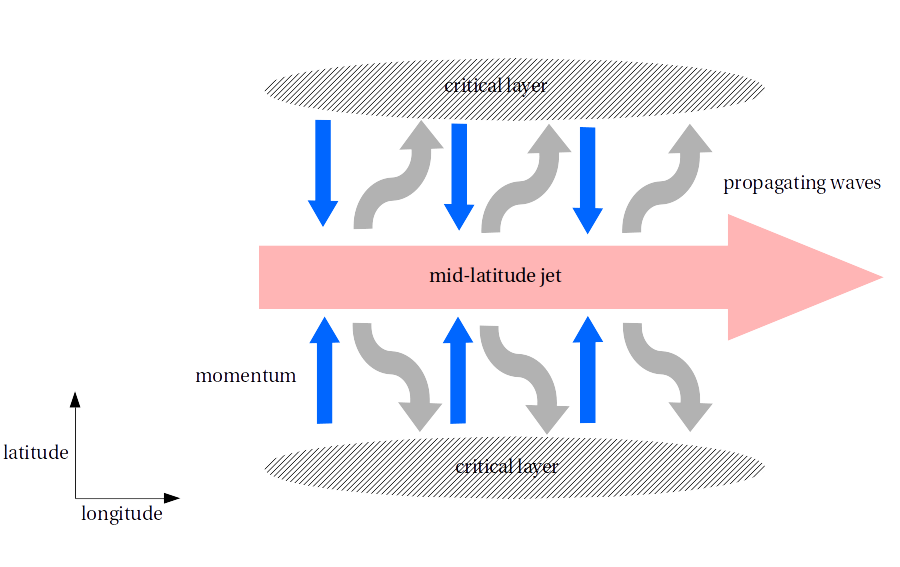

There are several different theories for why jets shift, but no consensus. To put these together I find it helpful to use this schematic of the dynamics of the mid-latitude upper troposphere:

This is the classic picture of a baroclinically unstable source region – the jet – where eddies (Rossby waves) are excited and then propagate away. The eddies break at lower and higher latitudes and flux momentum back into the jet. With this picture, jets could shift because of shifts of the source region or of the sink regions, which affect the eddy momentum fluxes that drive the jet.

Background: the zonal-mean structure of global warming

The jets feel the effect of global warming through the structure of the temperature response in height and latitude. The latitudinal variations in the response are particularly important, since the zonal wind is connected to the meridional temperature gradient by the thermal wind relation: $$ \frac{\partial u}{\partial z} \sim \frac{\partial T}{\partial y} $$

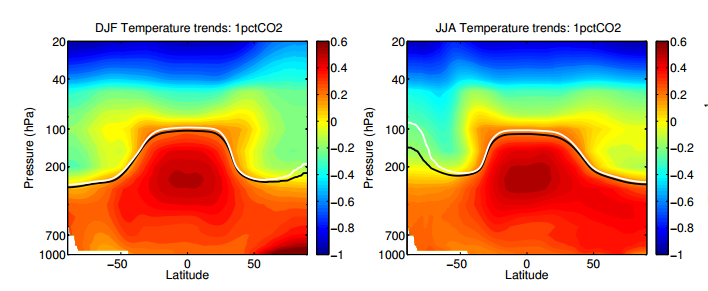

With global warming the largest warming is in the tropical upper troposphere and, in northern hemisphere winter, in the high-latitude lower troposphere:

(Figure 6 from Vallis et al. (2015). Sorry for the jet colormap.)

In the upper troposphere the meridional temperature gradient increases because of the enhanced tropical warming, and we expect the mean winds to accelerate in the upper troposphere/lower stratosphere. In the lower troposphere the meridional temperature gradient is weakened because of the high-latitude warming, resulting in a reduction of low level baroclinicity. During El Nino events there is also enhanced warming of the tropical upper troposphere, but over a narrower range of latitudes, and this difference is probably key to the opposing responses of the jet.

Moving the sinks

The dispersion relation for a Rossby wave is: $$ c = u - \frac{\beta}{K^2} $$ with \(u\) the zonal-mean zonal wind, \(c\) the phase speed of the wave, \(\beta\) the meridional gradient of the Coriolis parameter and \(K\) the total wavenumber. Rossby waves break at their critical latitudes, where \(u \sim c\) and \(K\) goes to infinity (these are also called critical layers). So shifts of the sink regions are due to some combination of changes in the waves' phase speeds and changes in the zonal-mean wind.

- Chen and Held (2007) (see also Chen et al. (2008))\) focus on the breaking region on the equatorward side of the jet. This seems like a good starting point because Earth's spherical geometry means that eddies preferentially propagate equatorward, and the largest eddy momentum fluxes are on this side of the jet.

Chen and Held make a relatively simple argument: because the subtropical winds accelerate, the equatorward critical layer (where \(u = c\)) moves polewards, and waves break closer to the jet. This effectively shifts the eddy momentum fluxes into the jet polewards and the jet shifts as well. - Kidston et al. (2010) make an argument based on changes to eddies’ phase speeds. They focus on the \(K\) term in the dispersion relation and suggest that, as a result of global warming, eddies get larger (\(K\) gets smaller). If eddies’ size is set by the first baroclinic Rossby radius:

$$

\lambda_R = \frac{NH}{f}

$$

with \(N\) the static stability, \(H\) the height of the tropopause and \(f\) the coriolis parameter; then since the tropopause rises under global warming (see the Vallis et al. paper for an explanation of why this happens), \(\lambda_R\) increases and, equivalently, \(K\) decreases. This slows down the eddies’ phase speeds, so eddies actually break further from the jet.

Kidston et al. then point out that the sink region on the poleward side of the jet overlaps with the source region. Since eddies are able to propagate further in a warmer world, they break further from the jet and this overlap is reduced. This increases the net eddy momentum flux on the poleward side of the jet, which shifts poleward.

This might seem to contradict the Chen mechanism, but Kidston et al. argue that both can be true at the same time. The acceleration of the subtropical winds could cause the critical layer on the equatorward side of the jet to move polewards, while at the same time the deceleration of the eddies could cause the poleward critical layer to move to higher latitudes, so both sinks shift poleward. - Related to the idea of eddy length-scales mattering, Riviere (2011) focused on how individual eddies break. Eddies which break anti-cyclonically tend to propagate equatorward, producing a poleward eddy momentum flux, while eddies which break cyclonically tend to propagate polewards and flux momentum towards the equator. Since long-wavelength eddies are more likely to break anti-cyclonically, an increase in eddy length-scales could increase anti-cyclonic wave-breaking, which would result in a poleward movement of the jet.

- A different perspective is to focus on wave reflection. This happens when \(\beta / K^2\) is larger than \(u\) and \(c\) changes sign. Several studies have suggested than in a warmer world, particularly if the mid-latitude jet speeds up, more waves are reflected on the poleward side of the jet (see Simpson et al. (2012) and Kidston and Vallis (2012)). This means there are more equatorward propagating waves and a larger net poleward momentum flux across the jet.

Moving the source region

The other approach is to focus on the baroclinic stirring which is the source for the eddies. The essence is that enhanced warming in the tropical upper troposphere results in a poleward shift of the maximum meridional temperature gradient in the upper troposphere which, combined with an increase in the static stability of the subtropics (see here), pushes the region of maximum baroclinicity polewards. A number of papers have attributed the poleward shift to this movement of the baroclinicity, including Lu et al. (2008), Butler et al. (2010), Wu et al. (2011) and Tandon et al. (2013).

Teasing out the different mechanisms

All of these mechanisms probably play a role in the jet shifts, with different levels of importance. And their relative importances probably vary across models of different complexity. Figuring out which mechanisms are most responsible for driving the shift isn't easy though. For instance, Robinson (2000) showed how an initial jet shift can cause a shift of the low-level baroclinicity, which feeds back on the jet shift. Barnes and Hartmann (2011) suggest that the poleward jet shift itself actually causes eddy length-scales to increase. There are a lot of things to untangle in this wave-mean flow problem. Nevertheless, some attempts have been made to separate out the different effects:

- David Lorenz used a technique called Rossby wave chromatography to track how individual wavenumbers behave. This let him look at how different eddies influence the jet (though not at changes in the stirring), and Lorenz found that increased reflection is the key factor in the jet shift. The caveat is that these results come from a barotropic model in which the stirring is prescribed.

- Another approach was taken in a series of papers by Gang Chen, Jian Lu and co-authors (e.g., here, here and here), who looked at the responses of the jet to global warming-like perturbations across a large number of transient simulations with different models. These seem to consistently show that shifts of the baroclinic generation zone lag jet-shifts. This implies that the direct cause of jet shifts is shifts of the sink regions, though exactly how this comes about seems to be model-dependent.

More than anything, what we need is a quantitative theory for the baroclinic stirring: what sets the strength and location of the source region. We might expect this to shift poleward because of changing temperature gradients, but we can't predict how changes in jet speeds and eddy properties will affect this, and are forced to rely on model simulations.

Another issue is that these theories are all based on dry dynamics. To fully understand – and predict – the jet shifts we also need to understand the roles of water vapor and clouds (Ceppi and Hartmann (2016) is an example of a study looking at the role of clouds). The stratosphere also influences the jets, and it seems like the recovery of the ozone hole will push the southern hemispheric jet equatorward a bit over the next few decades. Finally, there's the problem of internal variability: how long it takes for jet shifts to be clearly discernible from the noise (if they ever are), and whether the jets' internal variability can be leveraged to predict how the jets will shift, using ideas like the fluctuation-dissipation theorem.