The Arctic warms faster than anywhere else on Earth in response to increased CO2 concentrations. This is seen in observations, comprehensive climate models and in idealized models, but we still don’t have a great understanding of what causes this polar (or arctic) amplification of warming. One reason why it’s hard to understand is that different processes are responsible for polar amplification in idealized models than in more realistic model, so it’s hard to build “simple” models of polar amplification.

Two obvious candidates for causing arctic amplification are the ice-albedo feedback and the Planck feedback. The ice-albedo feedback is just that sea-ice cools the high latitudes by reflecting incoming solar radiation, so if sea-ice melts because of global warming high latitude warming is enhanced. The Planck feedback comes from the fact that black bodies emit radiation as temperature to the fourth power (T4). If we approximate the Earth as a black body, then colder regions have to warm up more than hotter regions to compensate for the same forcing.

But neither of these turns out to be the most important effect. The Planck feedback is actually quite weak, and ends up being overwhelmed by the forcing, which is tropically-amplified. The ice-albedo feedback plays a bigger role, but two analyses (Pithan and Mauritsen (2014) and Stuecker et al. (2018)) of comprehensive models have found that – in climate models – the lapse-rate feedback contributes the most to polar amplification. The lapse-rate feedback is negative in the tropics and positive at high latitudes: at low latitudes lapse-rates decrease, so the surface doesn’t have to warm as much to maintain energy balance at the top of the atmosphere, while at high latitudes lapse-rates increase, so the surface has to warm up more.

We understand the low latitude part of this well. Temperature profiles at low latitudes follow moist adiabats, and when the surface warms up the profiles shift to warmer moist adiabats, with smaller lapse-rates. The high latitude part is more difficult to understand.

Cronin and Jansen showed that the high latitude troposphere is in radiative-advective equilibrium, with radiative cooling balanced by poleward energy transport (here and here). This suggests that changes in polewards energy transport could be important for the positive lapse-rate feedback at high latitudes. But Stuecker et al. recently did an experiment in which CO2-like forcing is only applied at high latitudes, and found that this gives a strong positive lapse-rate feedback, even though the change in horizontal energy transport is small (and in the opposite direction from under global warming).

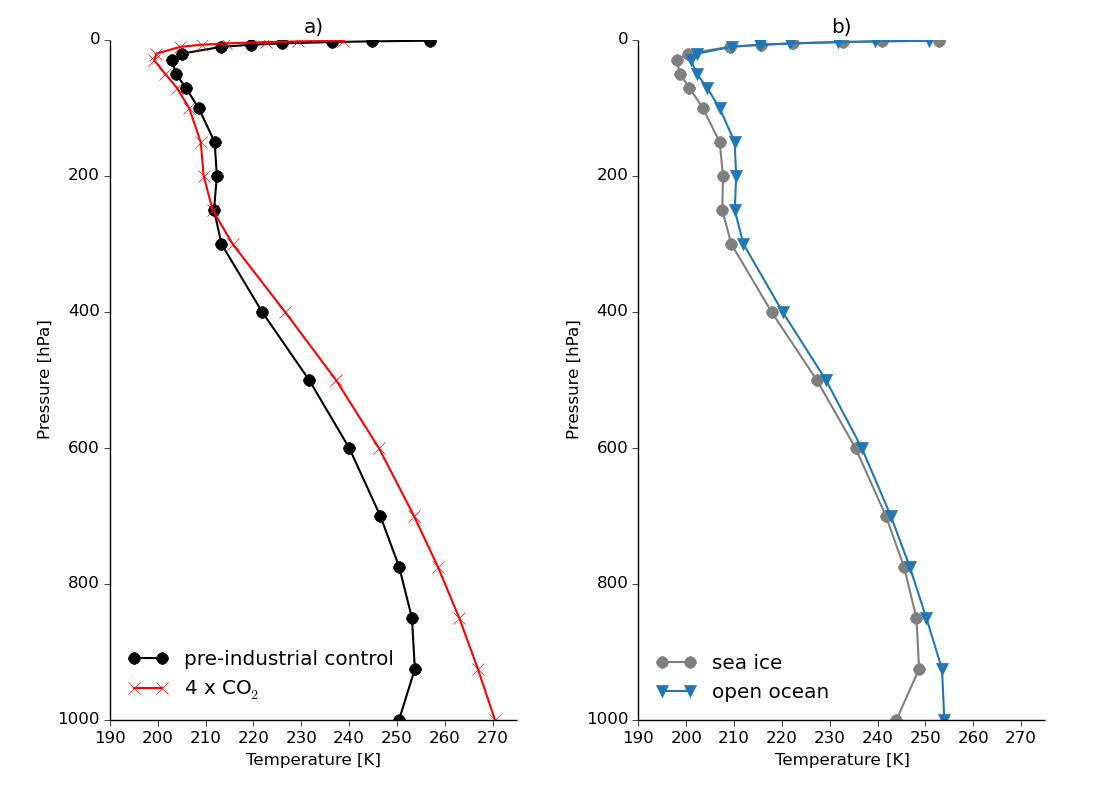

So local processes must be important for the high latitude lapse-rate feedback. We can bring in some other information to try to understand this: we know that polar amplification is mostly localized to near the surface and that it mostly happens in the wintertime. Also, in winter there is a near-surface inversion in Arctic temperature profiles. You can see this in the black line in panel a of this figure, which shows temperatures averaged over 65°N from a pre-industrial simulation with GFDL’s CM3 model.

How is this inversion set-up? In winter the high latitudes don’t get any insolation, so apart from some downwelling long-wave radiation from the atmosphere, there’s nothing to heat the surface. But the surface does emit radiation, so it can cool rapidly. Over the ocean temperatures are pinned to the freezing temperature, but over ice they can get very low. Higher up, the atmosphere is optically thin, so it cools more slowly, resulting in an inversion (ref).

In other words, inversions will mostly be found over land and over sea-ice, but not over open water. This is shown in panel b of the figure, which plots temperature profiles averaged over open water in blue and over ice in gray from the same simulation. There’s a hint of an inversion over the water, but it’s much more well defined over the ice. (Note: I calculated these by mutliplying temperatures by the sea-ice concentration and by (1 - sea-ice concentration), so the temperatures are a little bit lower because of places where sea-ice is between 0 and 100%.)

If there’s less sea-ice then the Arctic-averaged temperature profile will look more like the open water profile, with a weaker inversion (red curve in panel a). In a conventional feedback composition, this would look like a positive lapse-rate feedback, but this seems a bit deceptive, because it would really represent changes in the relative fractions of sea-ice and of open ocean. (Alternatively, if the ice thins enough then the near-surface air could be warmed by the waters beneath the ice through conduction, giving a similar effect.)

Screen et al. (2012) did experiments which isolated the role of reductions in sea-ice with two different climate models, in which they kept greenhouse gas concentrations fixed, but forced the models with observed monthly Arctic sea-ice and SSTs from 1979 to 2008. This produced strong wintertime warming, localized to the near-surface. This warming was probably partly due to the ice-albedo feedback, but the reduction in the relative fraction of sea-ice compared to ocean water (and/or the thinning of winter sea-ice) probably also played an important role.

High latitude lapse-rates are sensitive to other things, like the radiative forcing, surface warming and atmospheric energy transport. But the erosion of the inversion because of changes in sea-ice is likely a major part of the positive high latitude lapse-rate feedback diagnosed in climate models. This also shows how the conventional ways of estimating feedbacks can be deceptive for understanding what’s actually happening.

(Thanks to Daniel Koll for helping me understand high latitude inversions)