Most of the excess heat gained by Earth is taken up by the oceans. This has (at least) two important effects on Earth's climate: (1) it raises sea-levels (by about 0.4m per K of warming), and (2) it slows the rate of increase of global-mean surface temperature (GMST). So measuring how much heat the ocean has taken up is important for understanding past and future sea-level changes and for predicting how temperatures might change in the future.

Ocean heat uptake is also a kind of “smoking gun” for global warming: it’s very hard for internal variability to create a situation in which both the ocean and the surface warm for long period of time. Something must be adding heat to the system.

Unfortunately, we only have near-global ocean data coverage since 2006, which limits how accurately we can estimate ocean heat uptake before then. Two recent papers try to address this issue by reconstructing past changes in ocean heat uptake: Zanna et al. estimated changes in ocean heat content (OHC) since 1871, while Gebbie and Huybers went all the way back to 0 CE. Interestingly, these studies used very similar methods to do their reconstructions. Both assumed that heat anomalies are advected as passive tracers in the ocean, and that variations in ocean circulation have been small over time. They then used (time-independent) models of ocean transport to propagate sea-surface temperature anomalies, averaged over large patches, down into the ocean, giving estimates of the 3D temperature structure of the entire ocean in the past.

Besides using similar methods, both studies used the HADISST dataset for SSTs since 1871, and Gebbie and Huybers then added the Ocean 2K SST network (a synthesis of different SST reconstructions over the last 2000 years) to go back to 0 CE. Zanna et al. built their ocean transport model from the ECCO dataset, and Gebbie and Huybers used the WOCE dataset. Gebbie and Huybers also compared their results with depth profiles of ocean temperature collected during the world-wide expedition of the HMS Challenger, which allowed them to test their reconstruction for the period 1872-1876.

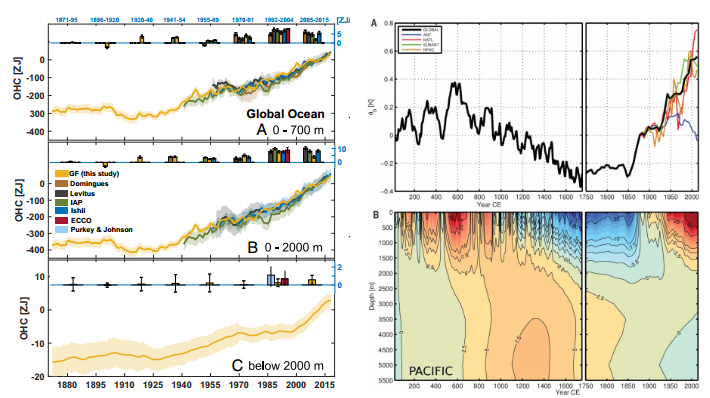

Zanna et al focused on changes in OHC since 1871, and found that this was relatively stable between 1871 and about 1920, then increased until about 1955, when it was flat for a while, then picked up again around 1980.

(Adapted versions of Figure 1 from Zanna et al. (left) and Figure 1 from Gebbie and Huybers (right)).

Gebbie and Huybers were interested in even longer term trends, though their results are fairly similar from 1871 onwards (there's actually a jump in their reconstruction between about 1850 and 1871 – maybe because the HADISST data starts being assimilated?). The main punchline is that there was global ocean cooling between the Medieval Warm Period (~950 to 1250CE) and the Little Ice Age which followed and that, because the ocean takes hundreds to thousands of years to come into equilibrium, the effects of this cooling are still being felt. Surface waters and the deep Atlantic have adjusted to this cooling, but the deep Pacific is still responding: although the surface waters of the Pacific are warming, below about 2000m the Pacific is cooling. This effect is pretty small (1/100s of K), but integrated over the whole Pacific it offsets about 25% of the increase in OHC since 1750 (Zanna et al. have a plot of the deep Pacific's OHC in the supplementary material, but it’s hard to see if there’s a trend).

A caveat to both results is changes in ocean circulation. Zanna et al. addressed this by comparing with direct reconstructions, which in-fill 3D ocean temperature observations and go back to 1955. This showed that the effects of circulation changes averaged over individual basins are small, but that these do affect regional patterns of ocean heat uptake. For instance, up to 50% of the warming in the Atlantic between 20 and 50\(^\circ\)N came from changes in ocean circulation.

Gebbie and Huybers did sensitivity tests to see how changes in ocean circulation affected their results, for instance by assuming that ocean circulation strength linearly co-varies with global-mean surface temperature. While this does change things, their main result, that the deep Pacific is cooling, still holds in the sensitivity tests.

Some Comments

- Ocean heat uptake seems to track changes in GMST pretty well. Zanna et al. note that the increase in OHC from 1921 to 1946 is comparable to that between 1990 and 2015, and the increases in GMST in these periods are also similar (about 0.3K, see here).

- Zanna et al. show that changes in ocean transport have impacted regional sea-levels, contributing up to about 50% of regional changes in sea-level since the 1950s. This adds to the regional differences in sea-level rise due to the gravitational pull of ice sheets (the Greenland ice sheet pulls water to it, so if it melted sea-level around Greenland would actually decrease), and the fact that the solid Earth is still adjusting to the melting of the ice sheets from the last Glacial Maximum (see here for more).

- Gebbie and Huybers note that the cooling of the deep Pacific needs to be incorporated into historical climate model simulations, since without this the modelled ocean heat uptake will be much larger than it actually was. This would affect the inferred equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS, the equilibrated response of GMST to an abrupt doubling of atmospheric CO\(_2\) concentrations) in these esimulations. ECS can be inferred from transient perturbations as $$ ECS = F_{2x} / (F(t) - H(t)) \Delta T, $$ where \(F_{2x}\) is the radiative forcing from doubling CO\(_2\), F(t) is the radiative forcing at time \(t\), H(t) is the net ocean heat uptake and \(\Delta T\) (t) is the response of GMST at time t. So if simulations have articially large \(H\)s, their inferred ECSs will also be larger (N.B. the inferred ECS is not the same as the actual ECS).

- Similarly, the cooling of the Pacific suggests that the ocean is more out of equilibrium with the surface than would be naively expected. So there could be more ocean heat uptake in the future, and the ocean could take longer to come into equilibrium, than if there hadn't been a Little Ice Age.