One of the most important potential impacts of future climate change is on the water supply: will future climates be wetter or drier? Clearly, this has major implications for human life and for terrestrial ecosystems, and a particular worry is that warmer climates will experience more droughts (or even mega droughts).

It turns out that the answer depends on what we mean by "wetter" and "drier". For instance, one way to quantify these is with indices which measure the severity of droughts or which give some more general measure of how "arid" (dry and dusty) a climate is. Two commonly used indices are the Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) and the ratio of precipitation (P) to "potential evapotranspiration" (PET). We can also measure water availability and its impacts directly, through things like precipitation minus evaporation (P-E, equal to the river runoff) and net primary productivity (NPP). These correspond more closely to what we actually care about: river levels and plant growth.

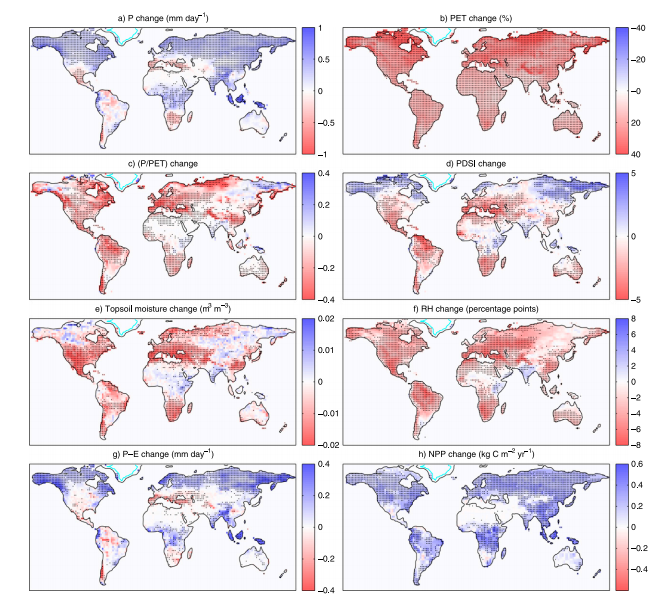

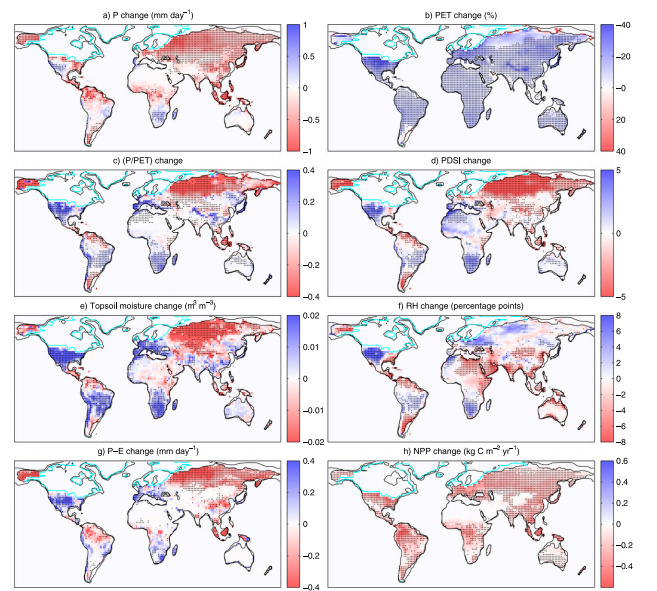

Climate models give different answers depending on whether we use indices or direct measurements. Models robustly project "drier" future climates in the sense of larger PDSI and smaller P/PET ratios. Going the other way, to cooler climates, they also suggest that the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, hopefully the last acronym) was wetter than today: PDSI was lower and P/PEI was higher. But P-E is more ambiguous, and NPP is projected to increase in future climates (Earth will get greener) and likely decreased in colder climates (Earth was browner) . Scheff et al. (2017) did a very thorough analysis of these, and you can see the differences between indices and direct measurements in model simulations of future warming (their Figure 1):

and of the LGM (their Figure 2):

There are several reasons why the indices predict drying at warmer temperatures. First, they have drying with warming "baked in" to them because of the intuition that warmer, sunnier conditions tend to enhance evaporation. So the indices are quite sensitive to temperature, and taking out this temperature dependence makes the wetting/drying signals weaker (Milly and Dunne (2016); see also this review).

Another factor is that we expect relative humidity to decrease over land. All else equal, lower relative humidities result in more evaporation, making land drier. Byrne and O'Gorman (2016) give a simple explanation for this reduction in relative humidity: assuming that the specific humidity over land is mostly set by the specific humidity over ocean (where most evaporation happens), relative humidity over land is proportional to the relative humidity over ocean times the ratio of ocean temperature to land temperature: $$ RH_{land} = \gamma RH_{ocean} \times T_{ocean} / T_{land}, $$ where\(\gamma\) is a constant of proportionality. Assuming changes in\(RH_{ocean}\) and\(\gamma\) to be negligible, the change in\(RH_{land}\) comes from the ratio of ocean warming to land warming. Since we expect land to warm more than the surface ocean (Byrne and O’Gorman again), this ratio decreases, and so does\(RH_{land})\.

Finally, the indices don’t seem to account for the effects of warming, and of higher CO\(_2\) levels, on plants. At higher CO\(_2\) levels plants’ stomatal conductance decreases – they lose less water to the atmosphere – and so plants retain more water, making land surfaces moister. Plants are also "fertilized" by higher CO\(_2\) concentrations: they need CO\(_2\) to grow, so higher CO\(_2\) levels encourage more plant growth. (Some important caveats are that these effects vary by plant-type and that plant growth can also be limited by other nutrients).

While NPP goes up almost everywhere, P - E is more ambiguous, decreasing with warming in some places, like the Amazon and the subtropics/mid-latitudes, and increasing in others, over equatorial Africa and at high latitudes. The changes in P - E are partly due to changes in plants, but we can also get some physical understanding by decomposing the changes into their thermodynamic component (changes in how much water the atmosphere holds) and their dynamic component (changes in circulation patterns). (Note that the P - E changes look a lot like the changes in precipitation).

We expect the deep tropics on the whole to get moister in the future, because of the thermodynamic effect (warm air holds more water vapor), but circulation changes can be important on a regional level. For instance, Figure 9 of Chadwick et al. (2013) suggests that the drying over the Amazon comes from shifts in deep convection such that convection is reduced over much of South America. I haven't found more about this, but it seems worth understanding better. Convection over equatorial Africa doesn't change as much, so the thermodynamic effect dominates there and P – E increases.

The drying of the subtropics/mid-latitudes comes partially from the thermodynamic effect – these regions are already dry, and they dry further in a warmer climate, following the "wet get wetter, dry get drier" rule of thumb – and partly because transient eddies export more water from the subtropics to higher latitudes. For the same reason, P - E is enhanced at high latitudes (see Figure 13 of Seager et al, 2010 for a breakdown).

Going back to the indices, these do have issues, but an important process they may be relevant for is fire. Fires tend to occur for warm, dry conditions – the kinds of conditions quantified by PDSI and P/PET. Past fire rates are hard to measure, but there's some evidence that there were fewer fires during the LGM than during the pre-industrial period (page 206 of Scheff (2018)), agreeing with the indices' claim that the LGM was wetter than today.

I also wonder whether the NPP and P-E changes in the figures above are somewhat misleading, because the plots show absolute changes, not relative changes. In regions with little vegetation (the Sahara, the Kalahari, etc.), where plants also don’t buffer the water supply, there may be more of a drying signal. But these regions have very small values of NPP and P-E (P - E is generally smaller over land than over the oceans), so changes there might not stand out as much as other regions. It would be particularly interesting to focus in on the borders of deserts, the regions where desertification may happen in the future. For instance, physical arguments suggest that the Sahel will become drier in a warmer world (see here).

In any case, future changes in water availability are much more ambiguous than changes in temperature, and the projected changes are sensitive to how water availability is quantified. The results summarized here are also at the resolution of climate models, but water is something we care about on a local level. At these smaller scales things might be quite different from the broad-brush pictures we get from climate models.