Equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) is the equilibrated warming of global-mean surface temperature in response to a doubling of CO\(_2\) concentrations. This important number is still quite uncertain, with a typical "likely" range being 2-4.5\(^\circ\)C. At the same time, we know that global-mean precipitation P increases by 1-3%\(^\circ\)C\(^{-1}\): if ECS = 4\(^\circ\)C, P increases by 4 - 12% after a doubling of CO\(_2\). So the precipitation sensitivity is the percentage increase in global-mean precipitation per degree of global warming.

Recently, Watanabe et al. (2018) suggested that there is an inverse relationship between ECS and precipitation sensitivity: models with a larger ECS (say 4\(^\circ\)C) should have smaller fractional changes in precipitation (say 1%), and vice versa. Their reasoning is that low clouds -- which are the largest source of uncertainty in ECS -- have the opposite effect on the warming of surface temperature as they do on precipitation.

The TOA Energy Budget

To understand this, let's think about the top-of-atmosphere (TOA) radiation budget and the atmospheric radiation budget. We can write a (linearized) version of the TOA budget as $$ R = F - \lambda T $$ where \(R\) is the anomalous TOA radiative flux (positive for flux out of the system), \(F\) is some radiative forcing, like an increase in CO\(_2\) concentrations, \(\lambda\) is a radiative restoring co-efficient and \(T\) is the anomalous global-mean surface temperature. After a doubling of CO\(_2\) concentrations this system equilibrates so that $$ T_{eq} = ECS = F / \lambda. $$ Most of the uncertainty in ECS comes from the feedback parameter \(\lambda\), which represents a sum of partial derivatives: $$ \lambda = -\sum_i\frac{\partial R}{\partial X_i}\frac{\partial X_i}{\partial T}, $$ with one of the \(X_i\)'s being cloud cover (\(C\)): $$ \lambda_C = -\frac{\partial R}{\partial C}\frac{\partial C}{\partial T}. $$ \(\lambda_C\) is the largest source of uncertainty in \(\lambda\), and hence in ECS, and most of this uncertainty comes from low cloud cover, whether this increases or decreases with warming.

From the TOA perspective the main effect of low clouds is to reflect solar radiation, increasing \(R\) so that \(\frac{\partial R}{\partial C} > 0\). If low cloud cover is reduced in a warmer world (\(\frac{\partial C}{\partial T}\) < 0) then clouds act as a positive feedback on warming (\(\lambda_C\) > 0), whereas clouds are a negative feedback if low cloud cover increases with warming.

The Atmospheric Energy Budget

The atmospheric energy budget can be written as: $$ LWC = LH + SH + SWA, $$ where \(LWC\) is the long-wave cooling of the atmosphere to space and to the surface, \(LH\) and \(SH\) are the latent and sensible heat fluxes, and \(SWA\) is absorption of short-wave radiation by the atmosphere. The latent heat flux is approximately equal to \(LP\), where \(L\) is the latent heat of vaporization of water, and so the change in precipitation is roughly given by: $$ \Delta P \approx (\Delta LWC - \Delta SWA) / L = \Delta Q / L, $$ as changes in the sensible heat flux are small, and with \(\Delta Q\) the net radiative cooling of the atmosphere.

Setting aside clouds for a moment, both \(LWC\) and \(SWA\) increase with warming, as a warmer atmosphere emits more longwave radiation and a moister atmosphere absorbs more shortwave radiation. In the net, the increased longwave cooling wins out, and precipitation increases.

(Note: it's not obvious why it works out this way -- why the cooling increases faster than the absorption -- but see Jeevanjee and Romps (2018) for an for a somewhat intuitive explanation for why we should expect this.)

Low clouds reflect incoming solar radiation, absorb upward longwave radiation emitted by the surface and emit long-wave radiation both upwards to space and downwards to the surface. Since these clouds emit at roughly the same temperature as the surface, the longwave radiation they absorb is roughly cancelled by their emission to space. The reflected short-wave doesn't affect \(SWA\) much, so in the net the most important effect of low clouds is to increase the atmosphere's longwave emission to the surface, increasing \(LWC\). Hence the change in atmospheric radiative cooling due to a change in low clouds is greater than zero: $$ \eta_C = \frac{\partial LWC}{\partial C} > 0, $$ and a reduction in low cloud cover with warming would lead to a reduction in precipitation (\(\Delta Q_{cl} = \eta_C\frac{\partial C}{\partial T_s} < 0\)).

So low clouds have the opposite effect on precipitation as on warming: a decrease in low clouds leads to a decrease in precipitation, and vice-versa.

Is There Actually An Inverse Relationsip?

If low clouds are the main source of uncertainty in ECS and in precipitation sensitivity, then this argument says that ECS and precipitation sensitivity should be inversely related in models: a model with a large reduction in low clouds under warming will have a high ECS and a low precipitation sensitivity.

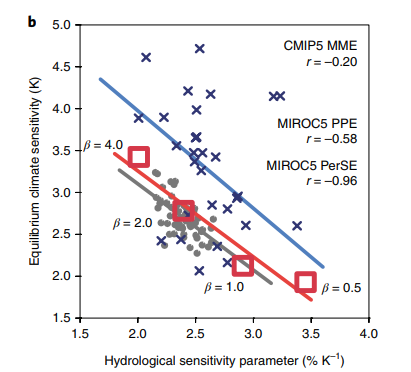

Watanabe et al looked into this in three ensembles of model simulations. First, they did an ensemble of simulations with the MIROC5 model in which the surface latent heat flux (the evaporation) was multiplied by a fraction \(\beta\). Increasing \(\beta\) increases the ECS and decreases the precipitation sensitivity, giving them exactly the relationship they were looking for (the PerSE regression in the figure).

(Figure 2b from Watanabe et al. Note, it's unclear to me why \(\beta\) increases ECS and decreases precipitation sensitivity. One guess is that larger surface latent heat fluxes enhance subcloud turbulence, which promotes stratocumulus break-up, as in Schneider et al (2019)).

Next, Watanabe et al compared the sensitivities across a perturbed physics ensemble with MIROC5, in which 10 different parameters in the convection scheme, the surface fluxes, etc., were varied. The correlation is not so strong in this set of experiments, but they still found a correlation \(r\) = -0.58. Finally, they looked at the CMIP5 data, where they only got a correlation \(r\) = -0.2.

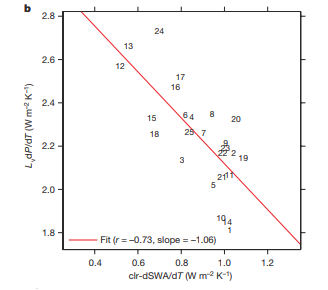

So this argument seems to work OK in a single model with varied parameters, but doesn't work across models. This is probably because low clouds aren't the most important source of uncertainty in precipitation sensitivity across models, or at least because other factors are also important. For instance, DeAngelis et al (2015) showed that there is a strong relationship across models between precipitation sensitivity and the sensitivity of clear-sky short-wave absorption to warming. In other words, \(\partial SWA_{cl} / \partial T\) is responsible for a lot of the spread in precipitation sensitivity:

(Figure 2b from DeAngelis et al.)

Much of the spread in \(\partial SWA_{cl} / \partial T\) comes from models using different radiation schemes, and DeAngelis showed that this could be improved if more models used good (correlated-\(k\)) radiation schemes. So potentially the spread in precipitation sensitivity due to shortwave absorption could be reduced, which might lead to a clearer inverse relationship between ECS and precipitation sensitivity. It will be interesting to check this once the data from the CMIP6 models is available.