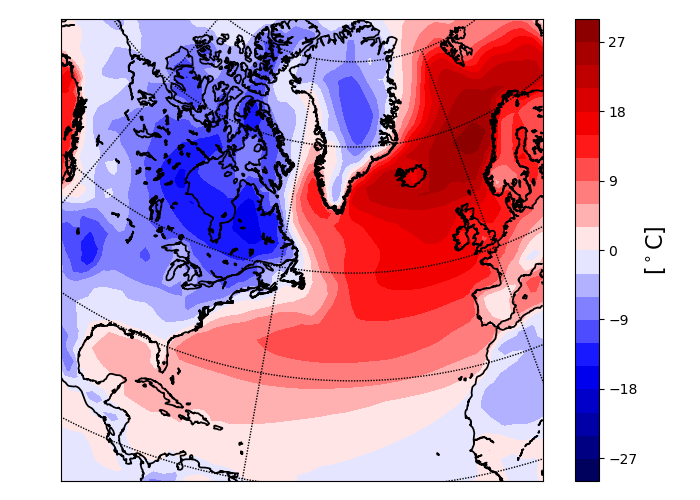

Lisbon is at roughly the same latitude as New York, but its average December daily low temperature is 9°C, whereas New York’s average December daily low temperature is 0°C. But in summer New York is actually slightly warmer, with daily highs of 28.9°C in July, compared to 27.9°C for Lisbon. Making a map of wintertime (December-January-February) temperatures shows that western Europe is typically 15-20°C warmer than eastern North America:

(Climatological DJF zonal anomalies in surface temperature in the North Atlantic sector, data taken from the ERA 20th Century reanalysis)

It’s often said that Europe’s mild winters are due to the Gulf Stream, which carries heat northeast from the southeastern coast of the US towards western Europe. This idea sometimes leads to panic that Europe would get much colder if the Gulf Stream “shuts down” as a result of global warming. But, while the intuition that the Gulf Stream is responsible for Europe’s mild winters makes some sense, we also know that at mid-latitudes the atmosphere transports much more heat than the ocean does (see here for a nice discussion). This makes it seem unlikely that the Gulf Stream is really so important for Europe’s winters.

In a seminal paper from 2002, Richard Seager and colleagues did a thorough investigation of what causes Europe to be so much warmer than North America in winter. They discussed three mechanisms which could warm western Europe:

- Heat transport by the Gulf Stream, which is then transferred to the atmosphere and advected over western Europe.

- Seasonal heat storage by the ocean: the ocean absorbs heat in summer and release it in winter, warming downwind regions (note that this does not require ocean currents or ocean heat transport).

- Atmospheric heat transport, and quasi-stationary waves in the atmosphere.

Using observations and various simulations (with/without ocean heat transport, and varying the mixed layer depths), Seager et al showed that the seasonal absorption and release of heat by the ocean has a much larger impact on regional climates than heat transport by ocean currents. They also ran simulations with the Rockies flattened, and found that the stationary wave forced by the Rockies strongly cools the East Coast and warms Europe (i.e., flattening the Rockies reduces the temperature difference).

Combining their results, Seager et al attributed roughly 50% of the winter temperature difference between eastern North America and western Europe to seasonal ocean heat storage, and roughly 50% to quasi-stationary atmospheric waves, with heat transport by the Gulf Stream playing a minor role.

Westward Radiation of Rossby Waves

In 2011, Kaspi and Schneider presented at alternative explanation for why North America is anomalously cold: heating of the atmosphere by warm ocean waters generates Rossby waves which radiate westward, cooling land to the west of the warm waters. So the Gulf Stream could excite a wave that cools the east coast of North America.

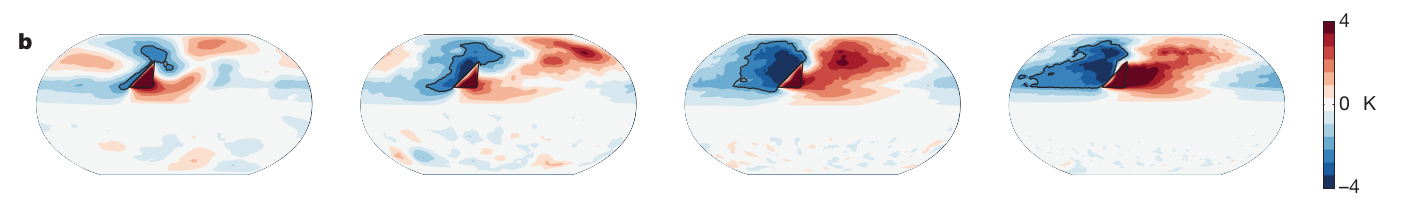

(Zonal surface temperature anomalies in idealized simulations from Kaspi and Schneider. The triangles are the “Gulf Stream” regions of anomalous warmth, and the rotation rate increases from 1xEarth to 8xEarth going left to right. Adapted from their Figure 2.)

While this is an elegant explanation, and works very well in the idealized simulations Kaspi and Schneider ran, it doesn’t seem like there’s much evidence for it in the Seager paper. In their simulation without ocean heat transport – i.e., with no Gulf Stream – the waters off the East Coast were cooler than in the control simulation, but temperatures over the East Coast didn’t seem to change much compared to the control simulation (Figure 12 in Seager et al). This suggests that the westward radiation of Rossby waves plays a secondary role, though it’s probably worth a more focused investigation.

Some New Simulations

The Seager et al study was published in 2002, and used relatively coarse models (one model had a resolution of 4° latitude by 5° longitude), so you might question the accuracy of their results.

In our recent paper on regional patterns of temperature variability, we did some simulations with a modern, high resolution (~50km) climate model – GFDL CM2.5-FLOR – including one with the Rockies flattened (thanks to Jane Baldwin who actually ran the simulations). Our focus was on temperature variability, but these simulations can also be used to estimate the impact of the Rockies on the temperature difference across the North Atlantic.

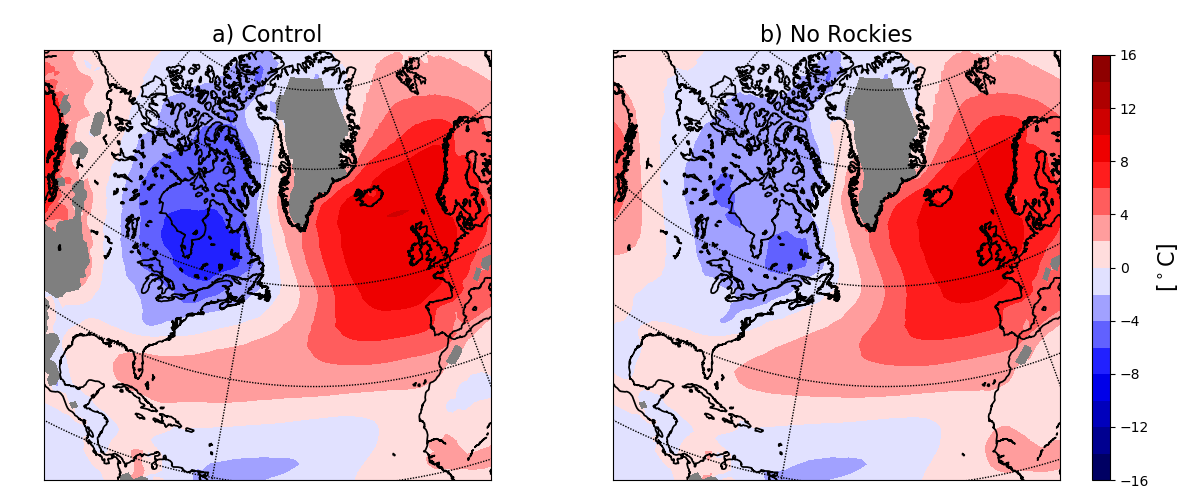

(Climatological zonal anomalies in DJF near-surface temperature from a control simulation with GFDL CM2.5-FLOR (a) and from a simulation in which the Rockies are flattened (b).)

The plot above shows the near-surface temperatures over the Atlantic sector for a control simulation and for the no-Rockies simulation. In the control simulation the largest temperature difference between eastern North America and Western Europe is 17.7°C, and this is reduced to 14.5°C in the no-Rockies simulation, mostly due to warming of North America. Western Europe isn’t strongly affected in this model by flattening the Rockies.

Comparing with Seager et al’s Figure 14, they also found that flattening the Rockies mostly warms the East Coast, rather than cooling Western Europe, but they found a much larger effect than we get in these high resolution simulations. So instead of attributing ~50% of the temperature difference to the Rockies, we get roughly 20%.

This doesn’t mean that the Seager study is wrong; heat transport by the Gulf Stream still probably isn’t the correct explanation for the relatively mild winters in Europe. But the relative importance of ocean heat storage, orography and other factors may differ from what Seager et al found. And a “Day After Tomorrow” scenario, with Europe freezing because of a shutdown of the Gulf Stream is still very unlikely.

(Jane and I are currently running simulations in which the sea surface temperatures in the Gulf Stream are smoothed out, which will allow us to check other aspects of the Seager et al results, and the Kaspi and Schneider mechanism. Stay tuned…)