People outside of climate science often worry as much about the high end of climate sensitivity estimates as they do about the mean of the estimates. As Wagner and Weitzman write in Climate Shock, risk is the likelihood of something happening multiplied by the damage if that thing happens. So the warm tail of the climate sensitivity distribution accounts for a lot of climate risk, since these scenarios would involve huge damages, even if they’re unlikely. Constraining the high end of climate sensitivity is hard, but is something we should maybe be putting more effort into. (Carbon cycle feedbacks which would also lead to large warmings, like melting methane clathrates, are another issue.)

A recent study related to the issue of the high end of climate sensitivity is Schneider et al. (2019), who used an idealized “climate model”, consisting of a deep convection box, like what is seen over the warm pool in the western Pacific, coupled to a high resolution (LES) box, representing the low cloud decks of the east Pacific. Low clouds cool the planet by reflecting solar radiation, and are the main source of uncertainty in climate sensitivity, with high climate sensitivity models showing reductions in low cloud cover with warming, and low climate sensitivity models showing increases in low cloud cover.

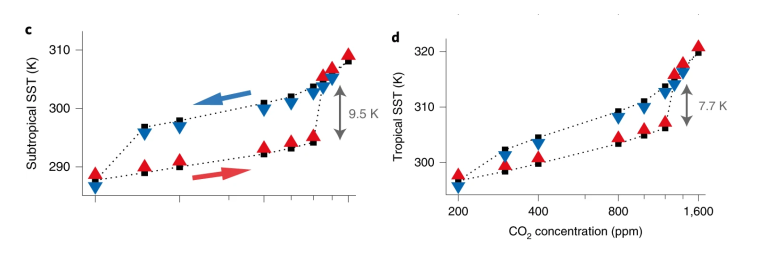

Schneider et al's LES model produces very detailed (and, by implication, realistic) simulations of low clouds, and they explored how the model's low clouds changed as the CO\(_2\) concentration is ramped up. Worryingly, the low clouds became unstable and dissipated when the CO\(_2\) concentration was increased to 1200ppm, leading to a jump of about 8°C in the model’s climate sensitivity:

(Modified version of Figure 3 from Schneider et al.)

This is a worst-case scenario for what a very high climate sensitivity world would look. The paper got quite a bit of pushback, but I think it was mostly meant as a proof of concept for their model, and the 1200ppm level shouldn't be taken too seriously. Paleoclimate data suggest that Earth's climate has been stable in the past with higher levels of CO\(_2\), though these come with their own caveats.

What’s interesting is that the jump came at a tropical sea-surface temperature of around 305K. A number of other studies looking at climate sensitivity across a large range of warmings (CO\(_2\) increases or increases in solar insolation) have also found maxima somewhere between 305 and 320K:

| Study | Maximum ECS | Temperature of maximum ECS | Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leconte et al. (2013) | 7K | 310K | LMD GCM |

| Mauraner et al. (2013) | 6K | 313K | 1D RCE model (based on ECHAM6) |

| Russell et al. (2013) | 8K | 313K | GISS‐AOM |

| Wolf and Toon (2015) | 8K | 310K | CAM4 |

| Popp et al. (2016) | 6.5K | 320K | Modified ECHAM6 |

| Wolf et al. (2018) | 15K | 320K | CESM1 |

| Schneider et al. (2019) | 8K | 305K | Two-box/LES model |

| Romps (2020) | 5.5K | 310K | DAM RCE model |

Caballero and Huber (2013) found a climate sensitivity maximum at a lower global-mean temperature of 299K in simulations of the Paleogene, but this could be due to the way they set-up their model to make it match the Paleogene period. There is also some evidence from paleoclimate data of higher climate sensitivity in warmer climates. And in an early study, Hansen et al. (2005) found a jump in climate sensitivity at 8xCO\(_2\).

(Please let me know about other studies I’ve missed. Also, note that the temperatures of maximum ECS mean different things in these studies: some are global-means and some are representative tropical values from RCE simulations.)

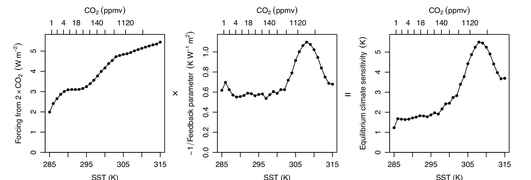

These maxima seem to be caused by minima in climate feedbacks, rather than by peaks in radiative forcing. The radiative forcing from doubling CO\(_2\) increases at higher and higher CO\(_2\) concentrations, but doesn't have a maximum in this temperature range:

(Figure 7 from Romps (2020))

Various reasons have been given for why the climate feedback has a minimum at warm temperatures:

- The jump in Schneider et al. clearly comes from the break-up of the low clouds, which they show is driven by two main processes. This break-up can only happen once, leading to a climate sensitivity maximum at that temperature. Wolf and Toon (2013) and Wolf et al. (2018) also attribute their sensitivity maxima to low cloud break-ups.

- Popp et al. focus on high clouds, showing that in their model deep convection spreads out into the subtropics, leading at first to a positive long-wave cloud feedback, which is eventually canceled out by a negative short-wave (high) cloud feedback at warm enough temperatures.

- Mauraner et al. ignore clouds, and attribute the high sensitivity to a strengthening water vapor feedback as the troposphere deepens, which is then reduced as the moist adiabat becomes increasingly steep and the amount of mass in the cold tropopause region diminishes. This weakens the water vapor feedback at high temperatures and results in a decreasing sensitivity.

- Russell et al. find that cloud feedbacks (both increases in high clouds and decreases in low clouds) and the water vapor feedback contribute to their sensitivity maximum.

- Caballero and Huber show that their climate sensitivity maximum is associated with a decrease in cloud cover throughout the tropics (where the reduction in low cloud cover presumably wins out), as well as with a decrease in cloud cover over the Southern Ocean.

Testing these different mechanisms further seems worth doing, especially with higher resolution global models (which can resolve low clouds), and with models that accurately simulate the radiative effects of high clouds. I am also curious what causes the sensitivity maximum in the DAM RCE simulations, which won’t have low cloud decks.

For strong enough forcing, Earth’s climate would probably runaway into a moist greenhouse state, like Venus’ atmosphere. But it seems that even before then, there would be a peak in climate sensitivity for a global-mean temperature near 310K (i.e., near 40°C), possibly associated with a rapid break-up of the low cloud decks and/or an increase in high cloud cover (I don’t understand the water vapor feedback mechanism very well). This might actually be good news, as we might still have a ways to go before hitting a dangerous climate sensitivity peak of 6+°C.