The concept of “model hierarchies” has been in vogue in climate science ever since Isaac Held’s seminal essay on “The Gap between Simulation and Understanding in Climate Modeling” (see also here). It is now very common for studies to include simulations with models of different complexity, which can mean different boundary conditions, different forcings, turning clouds on or off, etc. For the same reason, the development of new models is often motivated by a desire to fill in gaps in the hierarchy.

It seems to me that two of Isaac’s points often get lost in the rush to appeal to model hierarchies, however. The first is that the models included in the hierarchy should have lasting value: they must be simple enough that they are not affected by future developments, like increases in resolution, but they must also capture the basic physics we are trying to understand. In Isaac’s words, they should be “elegant”.

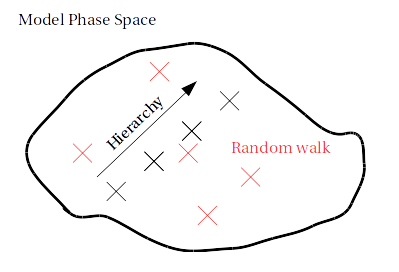

Another way to put it is that Isaac emphasized using “the” hierarchy rather than using “a” hierarchy. Having a canonical hierarchy focuses the community’s efforts, stopping us from going on a random walk through model phase space.

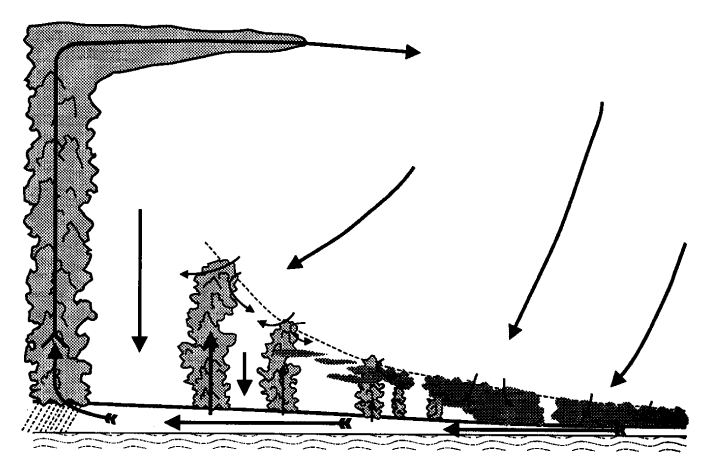

The other aspect of model hierarchies, which I think is implied in Isaac’s essay but not actually stated, is that they should be constructed to investigate a specific phenomenon. Isaac’s essay focuses on what he calls the “macroturbulence” of the atmosphere, the behavior of mid-latitude baroclinic eddies. The simplest model to study this is Phillips’ two-layer quasi-geostrophic (QG) model, which can be run on a laptop. The next level of the hierarchy is a dry primitive equation model on the sphere (usually run with the Held-Suarez forcing) and the gray radiation model then adds in the effect of latent heat release, before we get to comprehensive GCMs.

The point of this hierarchy is that the two-layer QG model can capture the basic features of the mid-latitude macroturbulence that we care about: baroclinic eddy life-cycles, the eddy momentum fluxes driving the jets, annular modes, etc. These phenomena are modified in more complex models, for instance through the addition of spherical geometry, but the same basic physics still operates. The annular mode in the QG model is very similar to the annular mode in the real atmosphere (though it generally has longer time-scales in the two-layer model).

Something I’ve been thinking about recently is how to develop a similar hierarchy for the tropical atmosphere. Many different models are used to study the tropical atmosphere, with different boundary conditions, boundary layer schemes, domain geometries; with or without rotation, with or without clouds, etc. This diversity of model configurations makes it hard to get an overview of what we actually know about the tropical atmosphere. Which results are robust across models? And how do they carry over into the real tropics?

(Note: I’m thinking here of understanding the mean state of the tropical atmosphere, not transient phenomena like the MJO and tropical cyclones.)

An example of this is the phenomenon of convective self-organization. This is seen in small domain cloud-resolving models in radiative-convective equilibrium (RCE) and global RCE models, and whether it occurs or not depends on the model resolution, domain size and average surface temperature. We also know that it is caused by longwave cloud radiative effects (see here for an entry into the literature). But its relevance to the real world is still unclear. Is self-organization an artifact of the models? Or is there something fundamental about it?

The problem is we don’t have a standard hierarchy connecting RCE models to the real tropical atmosphere. One reason for this is the separation of scales in the tropics. The state of the tropical atmosphere is determined by the microphysical processes operating in clouds, by cloud-scale processes like entrainment and by the large-scale tropical circulation, and these are all tightly coupled. A useful representation of the tropical atmosphere needs to include all these processes, which is an issue since they act on such a wide range of scales.

Another, related, reason for the lack of a hierarchy is that good (cloud-permitting) simulations of RCE have only been possible relatively recently (roughly the last 15-20 years). By comparison, the first QG models were developed in the 50s.

I think one other issue is exactly that RCE simulations do a good job of reproducing the basic features of the tropical atmosphere, like the average vertical profiles of temperature and moisture. But without a large-scale circulation, the convection has a lot of freedom in these simulations. In the real tropics, deep convection is basically confined to regions of large-scale ascent and shallow convection is confined to regions of large-scale descent; and the locations of these regions are set in turn by the SST patterns. By removing this structure, the convection in RCE simulations with uniform boundary conditions can organize itself however it wants, and one lesson from the self-aggregation literature is that this organization is very sensitive to how you set your model up.

Adding in a large-scale circulation removes this degree of freedom, or at least damps it. Allison Wing and Tim Cronin have shown that using long-channel domains, with one wide direction and one narrow, results in a realistic distribution of vertical velocities. I think that this should be taken further and more simulations should be run with SST gradients (the “mock-Walker” set-up), which also fixes the location of the circulation in space. (While tropical convection goes through significant re-organizations during ENSO events, this variation is slow compared to the processes which control the mean-state of the tropical atmosphere).

An analogy is that in the mid-latitudes we can “give” ourselves the temperature stratification in the two-layer model, because what we really care about is the dynamics. In mock-Walker simulations we give ourselves the basic structure of the convection, so that we can study the convection itself.

|

To get back to building a model hierarchy for the tropical atmosphere, there is a need for simplified RCE models, with idealized representations of cloud microphysics, radiation, cloud processes, etc. Since there probably isn’t a “best” way of doing this, the final forms of the models will come down to the community’s preferences. Further up the hierarchy, it seems like mock-Walker simulations (in 2D and in 3D) should be a prominent rung, since they are the most straightforward way of connecting small domain results to the actual tropical atmosphere. This will focus the small domain studies and stop the literature from getting too scattered. Finally, there are also some models which could take the place between the mock-Walker set-up and comprehensive models/observations, like David Neelin's QTCM model. These models haven't gotten much attention, but may be useful if it turns out that the mock-Walker set-up still lacks some important features.

(Note: the RCEMIP project, led by Allison Wing, is a useful effort in the other direction. That is, instead of building a model hierarchy, it looks at the range of model behaviors in small domain and long-channel RCE.)