How clouds change in a warmer world is one of the most important uncertainties in climate change projections. We're especially focused on how cloud cover changes, particularly low cloud cover, because even small changes in low clouds would have a big impact on how much Earth warms up in the near future.

One thing we can expect is that clouds will get denser in a warmer world, that they'll have more condensed water. Betts and Harshvardhan (1987) gave an explanation for why this happens, and Tim Cronin and I recently extended their explanation for more realistic assumptions in our paper on precipitation efficiency.

Clouds and the Saturated Moist Adiabat

The first reason why you might expect clouds to get denser in warmer climates is Clausius-Clapeyron: as air warms it can hold more water vapor, at about 7%K\(^{-1}\). But Betts and Harshvardhan explain that this isn't the right way of thinking about this. Instead, take a cloud that exists between two heights, \(z_1\) (the base of the cloud) and \(z_2\) (the top of the cloud). The base of the cloud is where rising air becomes saturated, so water condenses out as the air rises above \(z_1\). The total amount that condenses out is equal to the difference in how much water vapor the air can hold at the base of the cloud compared to how much it can hold at the top of the cloud (where the air is colder and so can hold less water vapor):

Mathematically, if we assume that the air is rising along a moist adiabat, then the condensed liquid water in the cloud \((l)\) is the difference in saturation mixing ratio between \(z_1\) and \(z_2\): $$ l \approx \left<\left(\frac{\partial q_v^*}{\partial z}\right)_{\theta_{e,s}}\right>\Delta z $$ where \(q_v^*\) is the saturation mixing ratio along the moist adiabat, \(\theta_{e, s}\) is the saturated equivalent potential temperature along the moist adiabat and \(\Delta z = z_2 - z_1\). The triangle brackets denote an average over \(\Delta z\).

Along a moist adiabat \(\theta_{e, s}\) is constant, so $$ \partial\theta_{e,s} = 0 = \frac{\partial \theta}{\theta} + \frac{L}{c_p T}\partial q_v^*, $$ where \(\theta\) is the dry potential temperature. This can be solved for \(\partial q_v^*\), and then we can substitute into the first equation: $$ l \approx \left<\frac{c_p T}{L\theta}\right>\Gamma_{\theta_{e, s}}\Delta z, $$ where \(\Gamma_{e, s}\) is the potential temperature lapse-rate \(\partial \theta / \partial z\) on the moist adiabat. The fractional change in \(l\) as a function of temperature is then $$ f_l = \frac{1}{l}\left(\frac{\partial l}{\partial T} \right)_{z_1, z_2} = \frac{1}{\Gamma_{\theta_{e, s}}}\frac{\partial \Gamma_{\theta, {e, s}}}{\partial T}. $$ \(f_l\) is always less than or equal to the Clausius-Clapeyron scaling of 7%K\(^{-1}\), and the difference between this scaling and the CC scaling increases as the temperature increases. In other words, the fractional increase in cloud density is smaller at warmer temperature. The dependence on pressure is more complex, but to give a number, for a cloud base at 800hPa and a temperature of 278.15K, \(f_l\) is 4.1%K\(^{-1}\).

Adding in Entrainment

An assumption in this derivation is that the rising air in the cloud doesn't mix with its environment, that there's no entrainment or detrainment. But we know that this isn't the case in reality, and that entrainment and detrainment play important roles in cloud processes. Most obviously, mixing takes condensed water out of the cloud, but entrainment/detrainment also affects the temperature of the rising air, so we can't just assume the temperature in the cloud follows a moist adiabat.

Singh and O'Gorman gave a way of calculating the temperature of an entraining plume, starting from the zero-buoyancy assumption. This sets the temperature of the rising air to be the same as the environment, so that the difference between the air in the cloud and the environment is just that the cloudy air has more water vapor.

For an entraining plume, the moist static energy is $$ \frac{dh_e^*}{dz} = - \varepsilon L_v(q_{v, e}^* - q_{v, e}) $$ where \(h_e^*\) is the saturated moist static energy of the plume, \(\varepsilon\) is the entrainment rate, \(L_v\) is the latent heat of vaporization, \(q_{v,e}^*\) is the saturated specific humidity of the plume and \(q_{v,e}\) is the mixing ratio of the environment. Subscript \(e\) denotes the environment and moist static energy \(h = c_pT + g z + L_v q_v\), with \(c_p\) the specific heat capacity of air and \(g\) the gravitational constant. The zero-buoyancy assumption sets \(T^* = T_e\) and \(q_{v}^* = q_{v, e}^*\) (the mixing ratio of the cloudy air is the saturation mixing ratio of the environment).

This expression can be re-arranged to get an expression for the water-vapor lapse-rate \(\gamma^* = \frac{\partial q_{v, e}^*}{\partial z}\) $$ \gamma^* = -\frac{c_p}{L_v}\Gamma_e - \frac{g}{L_v} - \varepsilon L_v (1 - RH)q_{v,e}^*, $$ where \(RH\) is the relative humidity and \(\Gamma_e\) is the environmental temperature lapse-rate \(\partial T_e / \partial z\).

The budget for the total water, the sum of water vapor and any condensed water, is $$ \frac{d q_t}{dz} = \frac{d(q_{v, e}^* + q_c)}{dz} = -\varepsilon(q_c + (1 - RH)q_{v,e}^*), $$ where \(q_c\) is the condensed water in the plume and I'm assuming that no precipitation falls out. The term on the right hand side is mixing out of water by detrainment. Substituting for \(\frac{dq_{v, e}^*}{dz}\) and re-arranging then gives $$ \frac{dq_c}{dz} = \frac{c_p}{L_v}\Gamma_e + \frac{g}{L_v} - \varepsilon q_c. $$ This equation can be solved by multiplying across by the integrating factor \(e^{\int \varepsilon dz}\) and integrating to give an expression for the condensed water at a height \(z' > z_1\). $$ q_c(z') = \frac{1}{e^{\int_{z_1}^{z'} \varepsilon dz}} \left[\int_{z_1}^{z'} \left(\frac{c_p}{L_v}\Gamma_e + \frac{g}{L_v}\right)e^{\int_{z_1}^{z'} \varepsilon dz}dz\right]. $$ (Note that in addition to appearing explicitly in this equation, \(\varepsilon\) also appears implicitly through its influence on the environmental temperature lapse-rate \(\Gamma_e\) (see equation 4 of Singh and O'Gorman).)

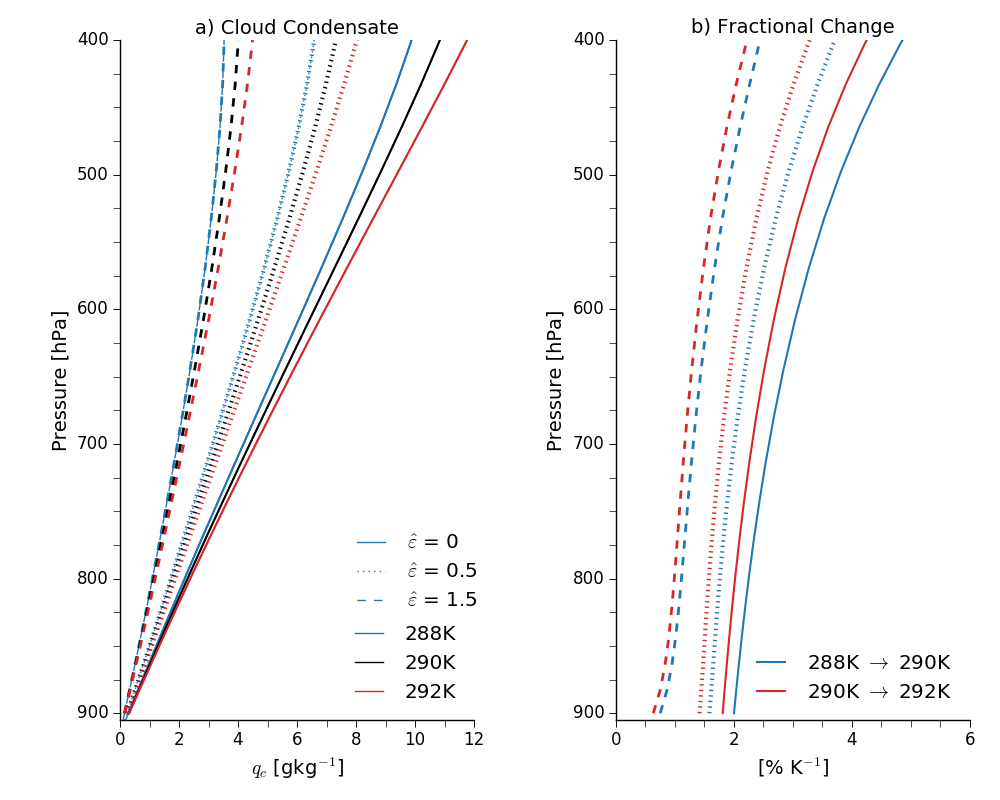

Now we can look at how cloud density varies as a function of temperature, pressure and entrainment (if \(\varepsilon = 0\) we get back the Betts and Harshvardhan scaling). Some examples are plotted here:

Panel a shows cloud condensate mixing ratios for plumes starting at 900hPa with an environmental relative humidity of 80% and with various cloud-base temperatures. I've parameterized \(\varepsilon\) as a decreasing function of height: \(\varepsilon = \hat{\varepsilon} / z\), and then also varied \(\hat{\varepsilon}\).

The cloud density increases with increasing temperature, agreeing with Betts and Harshvardhan's undilute (non-entraining) model, and decreases with increasing entrainment. This makes sense: if the entrainment was infinite we'd expect the cloud density to be zero.

Panel b shows the fractional changes with temperature. These get smaller for warmer cloud-base temperatures, again in line with the undilute model, and also get smaller with increasing entrainment. In other words, assuming entrainment is constant with warming, the increase in density of an entraining plume with temperature is less than for an undilute plume.

So clouds get denser for the reason identified by Betts and Harshvardhan, but this increase in density is reduced by entrainment. A caveat is that we've assumed that all the condensed water stays in the cloud, i.e., that none of it forms rain and falls out. The rate at which condensed water rains out is often taken to be proportional to the cloud density, so accounting for precipitation is tricky. Maybe it's better to say then that we can expect the total condensed water (cloud + precipitation) to increase in a warmer world.