"Superrotation" refers to atmospheric flows that rotate more quickly than the planet beneath them, creating an angular momentum maximum in the interior of the atmosphere (rather than at the surface). Earth rotates west-to-east, with the fastest rotation at the equator, so a superrotating atmosphere has west-to-east winds (\(u > 0\)) at the equator. (It's possible to have superrotation at higher latitudes, but this requires a very strong forcing to maintain it, since the flow would be inertially unstable.)

Mathematically, the angular momentum (\(M\)) of a shallow atmosphere is $$ M = (u + \Omega a cos\theta)acos\theta, $$ where \(\Omega\) is the angular velocity at the Equator, \(a\) is Earth's radius and \(\theta\) is latitude. At the equator, the surface angular momentum is \(M = \Omega a^2\), so superrotating flow has $$ u_s > a\Omega sin^2(\theta) / cos\theta. $$

Hide's theorem says that the mean flow cannot maintain a superrotation state, hence the only way to create superrotation is with (upgradient) eddy momentum fluxes. This is actually pretty common: the atmospheres of Venus, Jupiter, Saturn and Titan superrotate. People also get excited about superrotation because of the potential for bistability, as simple models often show superrotating and non-superrotating states co-existing for certain parameters (e.g., here). There are also ideas/evidence that superrotation was important for some paleoclimates and could reappear at very high CO\(_2\) concentrations.

So why doesn’t Earth’s atmosphere superrotate? To answer this, we have to go through the terms in Earth’s zonal-mean angular momentum budget: $$ \frac{\partial \bar{u}}{\partial t} = f[\bar{v}] - [\bar{v}]\frac{\partial [\bar{u}]}{\partial y} - [\bar{\omega}]\frac{\partial[\bar{u}]}{\partial p} - \frac{\partial}{\partial y}[\bar{u}^*\bar{v}^*] -\frac{\partial}{\partial p}[\bar{u}^*\bar{\omega}^*] - \frac{\partial}{\partial y}[\overline{u'v'}] - \frac{\partial}{\partial p}[\overline{u'\omega'}], $$ where \(v\) is the meridional (northward) velocity, \(\omega\) is the pressure velocity, overbars are time-means, square brackets are zonal-means, asterisks are zonal anomalies and \('\)s are anomalies from the time-mean. For simplicity I've written the budget out in cartesian co-ordinates and left out the the vertical Coriolis term, the metric terms and surface friction.

This leaves the \(fv\) term and then terms corresponding to the divergence of momentum by the mean horizontal flow, by the mean vertical flow, by the stationary eddies, etc. The horizontal transient term can be broken down further into a transient zonal-mean term and a transient eddy term: $$ [\overline{u'v'}] = \underbrace{\overline{[u]'[v]'}}_{\text{transient mean flow}} + \underbrace{[\overline{u'^*v'^*}]}_{\text{transient eddies}} $$

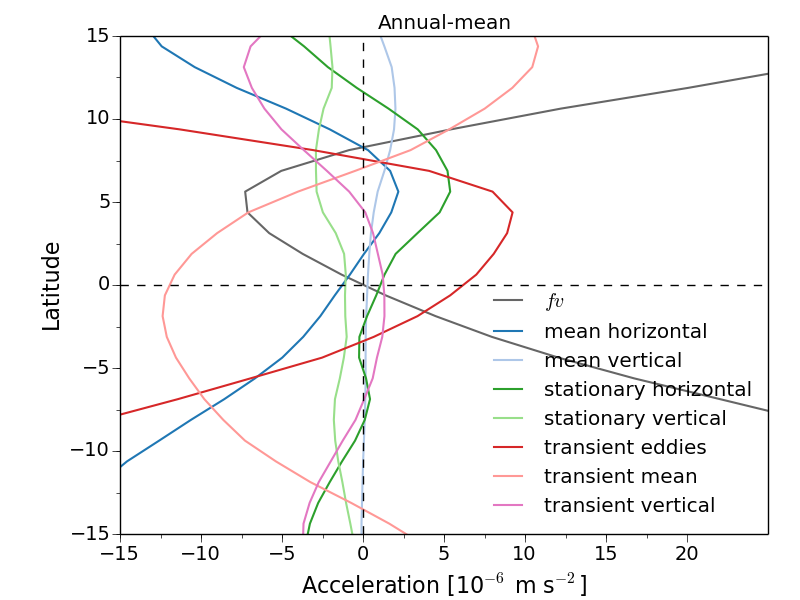

Lee (1999) showed that these transient terms are the dominant terms in the equatorial angular momentum budget. Here I've updated one of the figures, showing the budget at 200hPa and using data from the MERRA reanalysis:

You can see that the main balance is between the transient eddies, which accelerate the zonal-mean flow at the equator, and the transient fluctuations of the mean flow, which decelerate the flow. (Note that the mean vertical term is important lower in the atmosphere, where the rising branch of the HC brings up high angular-momentum air.)

What do these transient terms represent? Pablo Zurita-Gotor looked into the tropical eddy momentum fluxes in two papers last year (here and here), and found that they have a pretty complicated structure. The main way eddies flux momentum across the equator seems to be interactions between tropical stationary waves and zonal anomalies in the Hadley circulation (HC; i.e., correlations between the rotational zonal velocity and the divergent meridional velocity). On shorter time-scales, interactions between the MJO and the anomalous Hadley circulation also converge momentum into the equator, but this effect is smaller.

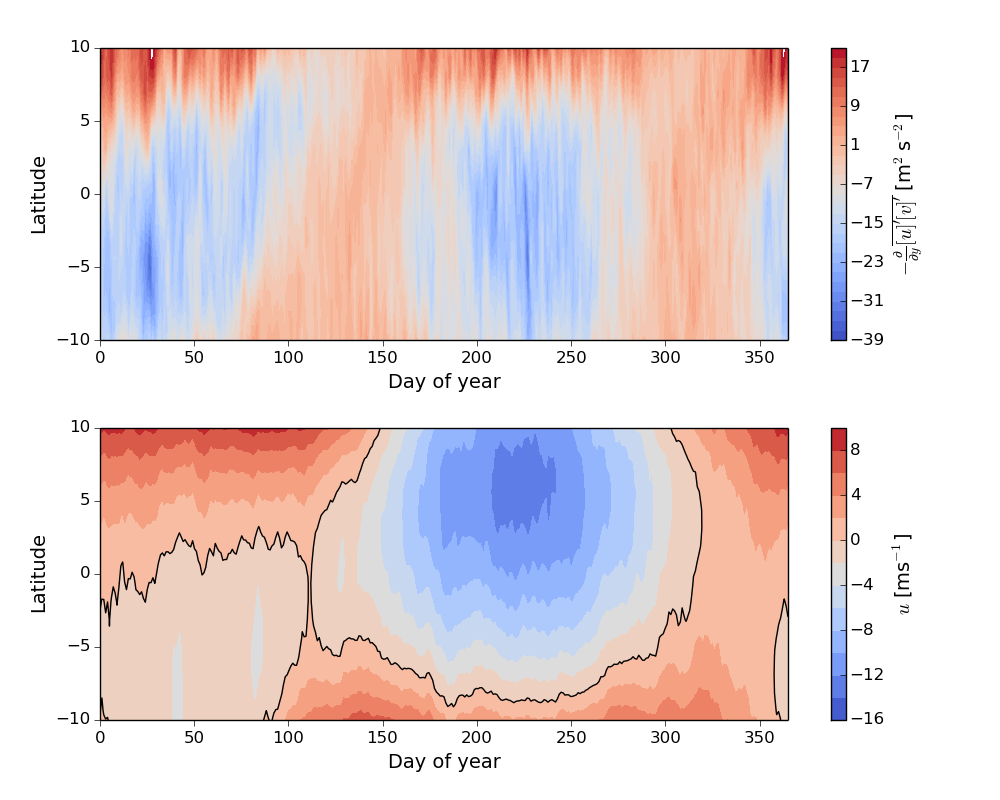

These eddy fluxes are balanced by fluctuations in the zonal-mean flow, which are really just the seasonal cycle of the HC. Here's what the divergence of the angular momentum transport by the zonal-mean HC looks like over the course of the year (top panel):

The largest divergences are in summer and winter. To understand this, note that the divergence of the eddy momentum flux is equal to the meridional vorticity flux, \(-\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\overline{[u'][v']} = \overline{[v'][\zeta']} \), where \(\zeta\) is the vorticity, and that for an angular momentum conserving flow, \(\zeta + f = f_0\), where \(f_0\) is the Coriolis parameter at the ITCZ (where the air rises). In Northern hemisphere summer \(f_0 > 0\) -- the ITCZ is north of the equator -- so \(\zeta\) is greater than zero, but \(v'\) is less than zero and so \( \overline{[v'][\zeta']} \) is also less than zero. In Northern hemisphere winter \(f_0 < 0\) -- the ITCZ is north of the equator -- so \(\zeta\) is less than zero but now \(v'\) is greater than zero and \( \overline{[v'][\zeta']} \) is still less than zero.

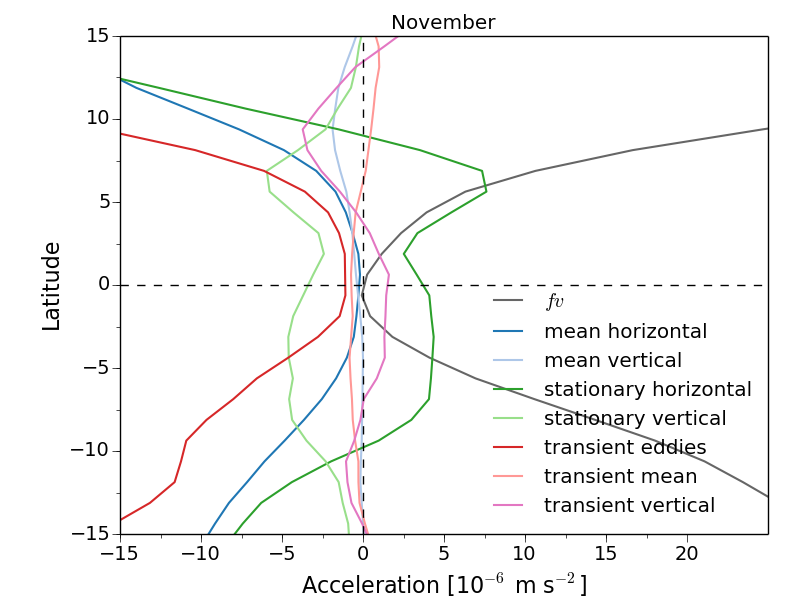

This argument comes from Lindzen and Hou (1988): when the ITCZ is off the equator, the HC transports low angular momentum air into the equator. However, this assumes an angular-momentum conserving flow, and when you look at the actual wind speeds, there is superrotation, on average, in winter and even in spring (bottom panel of above figure; the black contour marks the \(u\) = 0 line). Calculating the angular momentum budget for November (when the winds are accelerating) shows that stationary waves are driving the superrotation, while also redistributing the momentum vertically:

(Note that these stationary waves would show up as transient eddies when taking an annual-mean.)

To first order then, the main reason why Earth's atmosphere doesn't superrotate is that the ITCZ is north of the equator in the annual-mean. This means that the integrated seasonal cycle of the HC transports low angular momentum air into the equator (if the ITCZ was at the equator the HC transports would cancel out when integrated over a year). We'd get the same effect if there were no seasons and the ITCZ just stayed fixed north of the equator. Having said that, the HC isn't perfectly angular momentum-conserving, so to fully answer this question we have to understand how waves modify the angular momentum-conserving picture.

(Thanks to Pablo Zurita-Gotor for helpful discussions.)